For every dozen published hot takes and news peg-centric articles, there’s at least one or two pieces that seemingly appear out of the ether, the destined-to-go-viral expose on a small town gone rogue or a diamond-smuggling mafioso turned beloved middle school teacher. This series, Behind The Story, will unveil the origins of some of the more surprising or outlandish stories featured in The Sunday Long Read.

For more than five years, freelance journalist John Tucker has aspired to write a longform piece on sex-trafficking, but only recently did he find the source who turned his general topic into a real story. The resulting piece, “The Unlikely Story of a Sex Trafficking Survivor and the Instagram Account That Saved Her Life” about survivor and Avery Center founder Megan Lundstrom was published in Elle back in August. Journalist Sonia Weiser talked to him about the story.

Sonia Weiser: Where did the idea for this story come from? What was the order of events that led to you finding Megan?

John Tucker: Thanks for having me, Sunday Long Read! I’m a longtime fan.

I’d wanted to write a longform sex-trafficking story for more than five years, partly because it’s such a hidden crime, and partly because I felt like the definitive article—which in my mind needed to be told from the perspective of a survivor or trafficker—hadn’t been told, or at least I hadn’t seen it. (Coincidentally, I should acknowledge that the Washington Post also published last month a monster sex-trafficking piece, exposing the meager support systems that fail underage victims. It was written by Jessica Contrera, one of my favorite journalists these days, and is a masterful feat of reporting.)

Two years ago, I called the Polaris Project, a Washington anti-trafficking nonprofit. They told me that Seattle was doing great collective work to curb sex trafficking, and referred me to Ben Gauen, an assistant DA who worked exclusively on underage-victim cases. He offered several interesting angles, but when I traced down leads, none checked all the boxes I needed. A year ago I decided to check back in with Ben. He mentioned an uptick in trafficking cases involving sugar baby websites—platforms connecting older men with younger women in exchange for cash, and usually sex. This was interesting, but to tell that story I needed data, so I emailed the Polaris Project again.

And here’s where I say, props to the communications person! I’ve been a comms person at different points in my career, and it’s easy to feel like a middleman. But the Polaris Project comms person gets a star. She said she didn’t have any data to share about sugar sites, but suggested I reach out to Avery Center founder Megan Lundstrom, a former sugaring victim, for a survivor’s perspective.

I booked interviews with Megan and Angie separately and ended up speaking to Angie first. She revealed Megan’s secret Instagram account—and, as if that weren’t interesting enough, she explained how the account was the basis of bonafide academic projects. That’s when I knew I’d finally arrived at a story worth telling. The next day Megan and I clicked and the rest is history.

SW: This is your first story for Elle. What prompted you to pitch that publication over another? Was that the first publication you pitched the story to or were there others?

JT: This piece was rejected by two other publications before ELLE commissioned it. I figured Megan’s story would appeal to readers of women’s magazines, and ELLE has a track record of publishing ambitious, enterprising stories. So there was a respect factor.

There was nothing amazingly creative about the pitch itself. It was a basic summary of the narrative. I’m not sure if other writers do this, but in my pitches I include a mock hed and dek so it looks like a real entry point into an article. Here’s what I wrote:

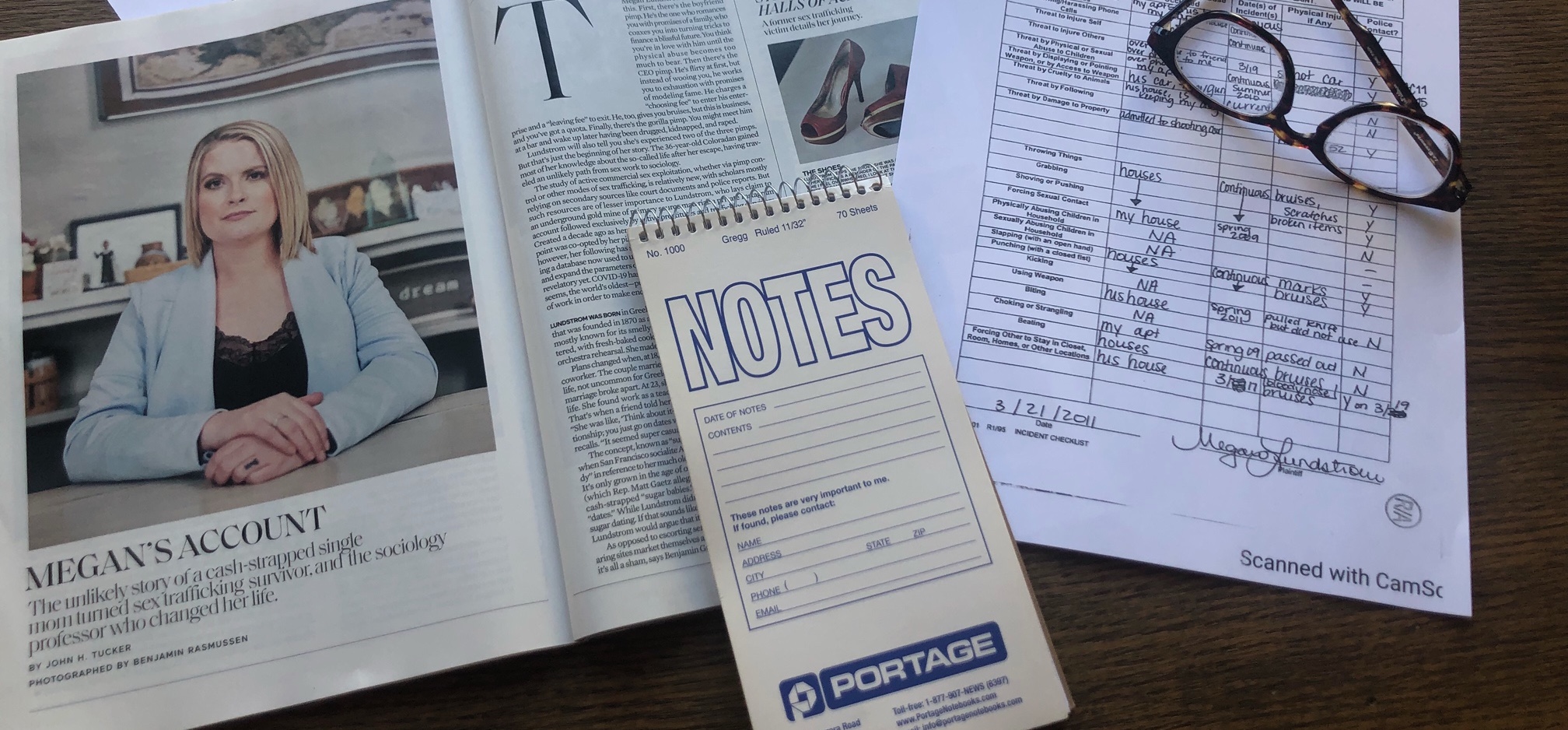

Megan’s Account

Megan Lundstrom’s Instagram account was monitored by her pimp and used to recruit prostitutes across the country. When Lundstrom escaped the life, she kept her account, now followed by more than 2,000 prostitutes and survivors. She uses it to aid trafficked women and expand the bounds of social science.

SW: How long did reporting take? How much of the research you included was info you found on your own vs. what you learned from interviews?

JT: I think I had six weeks between getting the assignment and turning in the first draft. I scheduled four hourlong interviews with Megan and one or two with Angie. I researched the issues as deeply as possible and called ancillary sources. I had a phenomenal editor, Melissa Giannini, and a powerhouse fact-checker, Laura Asmundsson, so the final product was a team effort.

SW: How did you decide on which other sources you’d contact for the story?

JT: I wanted readers to hear from a trafficked woman whom Megan helped, and I was grateful to find someone who offered that perspective, through tears—and said that yes, I could use her name, which was Lisa Junior. Beyond Megan and Angie, Lisa’s voice was most important to me. The rest of the sources who appear in the article just seemed like logical POVs to include without straying too far from the narrative.

SW: What was the hardest part of writing the piece from a purely technical standpoint?

JT: I wouldn’t call it the hardest part, but the corroboration phase of the reporting was time-consuming. This was a heavily fact-checked piece, relying on several off-the-record sources. Megan’s memory was accurate to a fault, which made things easier. She’d also saved many documents, which she shared with me.

SW: What’s it like to report on such a heavy topic?

JT: Yeah, I wouldn’t say I breezed through the reporting without any personal unease. When Angie cited qualitative data detailing women being raped in their cars in front of their kids, I felt physically ill for a moment.

In Megan’s case, she’s survived an unimaginable amount of trauma. But if you met her at the grocery store, you’d never know it. She’s down-to-earth, very funny and, as the piece shows, wicked smart. Those traits lowered the emotional toll for me, even as we went into graphic detail about her abuse. Because Megan is now a sociologist, she’s able to talk about disturbing things with clinical dispassion, and her unblinking, academic exploration into her history is precisely what allowed her to heal (though I would never presume she has completely healed or that the reporting process wasn’t at times triggering for her). One axiom she referenced, which I absolutely adored, was, “Research is mesearch.” That line sums up the whole story. Research is the opposite of suppression. The hope is that the message behind that line resonates with a handful of readers who can use it for their own personal growth, too.